By DAWN ROBIN MAGNESS

The natural landscapes of the Kenai Peninsula host about 60 percent of Alaska tree species, but when it comes to Populus, we have it all. Three species in this genus occur in Alaska and on the Kenai, quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides), balsam cottonwood (P. balsamifera) and black cottonwood (P. trichocarpa).

Populus trees are deciduous, meaning they have broad leaves that are lost each winter. Young trees have smooth bark.

Aspen are easily distinguishable from the cottonwoods. The species name, tremuloides, alludes to the unique qualities of the leaves. Aspen leaves are round and thin, yet slightly stiff. The stems are flattened.

A slight breeze will cause the entire tree to tremble or quake. The bark tends to remain smooth as the tree ages. Aspen can send out clone shoots and form large stands that are interconnected by a huge root system.

Balsam and black cottonwood are much harder to tell apart from one another. They look identical, except for minor differences in the flowers.

Both are large trees that grow quickly with bark that becomes furrowed with age. Both have sticky leaf buds and the female trees unleash cottony seeds from their long catkins. They are so similar that botanists sometimes lump them together as subspecies.

More often, they are considered separate species because of geographic separation. Balsam cottonwood is distributed across the boreal forest of Interior Alaska. Black cottonwood runs along the coasts through Southeast Alaska up to the Kenai.

Balsam and black cottonwood also have genetic differences. Genetic evidence linked to information about each species’ ecological niche supports the hypothesis that balsam and black cottonwood diverged about 75,000 years ago in the late Pleistocene.

At that time, ice rapidly expanded and the ancestors of these two species appear to have been geographically separated. Now that the ice has retreated, their distributions have expanded and touch along the margins. Balsam and black cottonwood can hybridize in the regions where they meet, such as the Kenai Peninsula.

In the 1970s, Leslie Viereck and Joan Foote collected cottonwood flowers in Alaska to map and describe the hybrid zone. They created a key to score if a flower was pure balsam, pure black or a hybrid.

Cottonwood trees are either male or female. Each cotton-producing catkin on a female tree consists of many small flowers. Balsam flowers are oval-shaped, leathery and split into two pieces (have two carpels) to release the seeds. Black cottonwood flowers are round, hairy and split into three or four parts, hence the name trichocarpa.

Viereck and Foote coarsely mapped the western lowlands of the Kenai to be a hybrid zone and the eastern side of the Kenai Mountains to be within the range of black cottonwood.

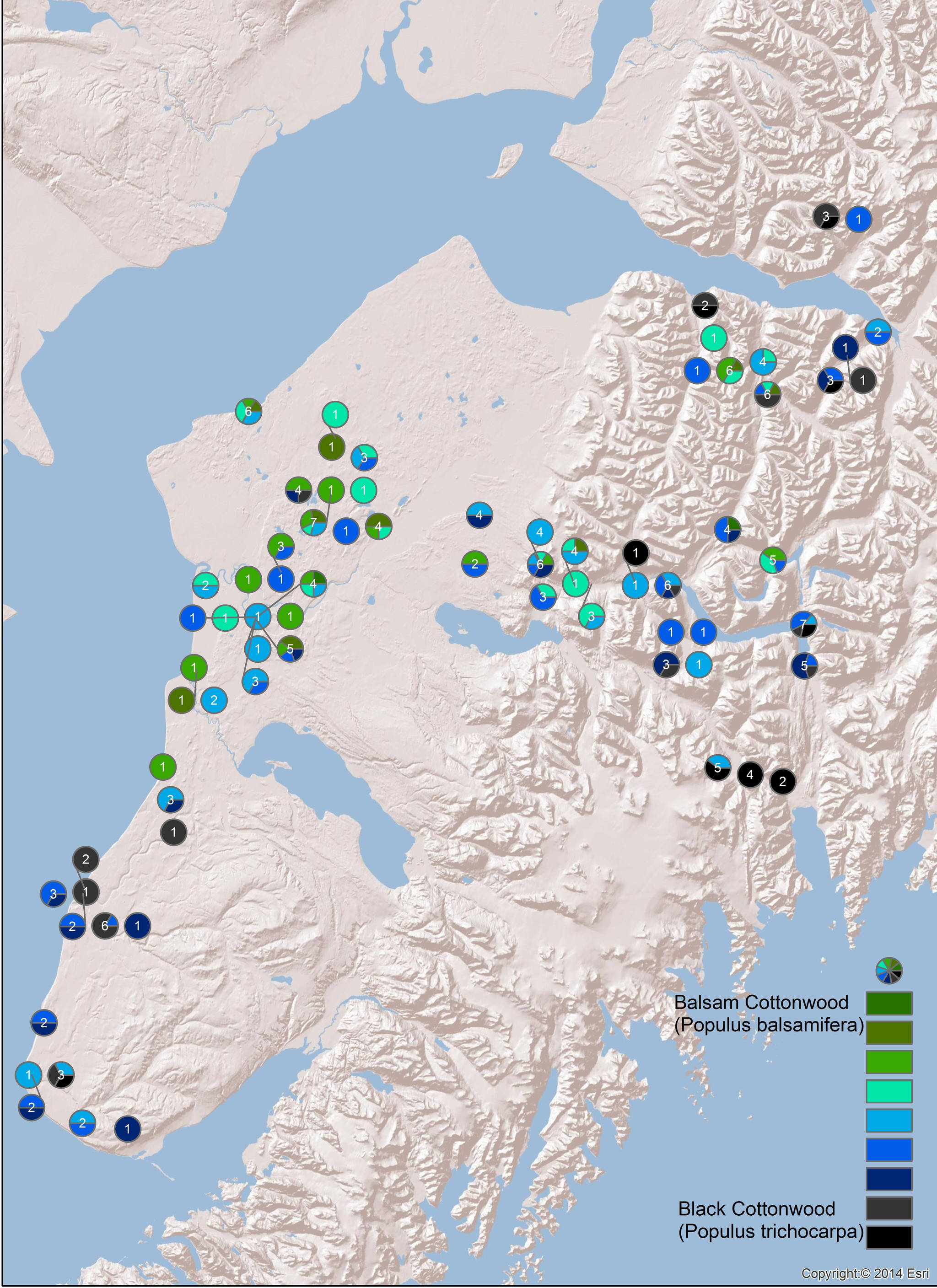

This summer, I collected catkins from nearly 200 trees across the Kenai to get a more detailed understanding of what and where cottonwoods currently occur. The map shows pie charts of the hybrid scores of trees for each location I sampled.

Within a stand, balsam and black individuals can be side-by-side with hybrids. Cottonwood pollen is wind-borne, so I expected that balsam and black trees would have no problem mixing together.

From my samples, the Kenai Lowlands north of Tustumena Lake tended to have balsam and hybrids transitioning to hybrids and black cottonwood south of Tustumena around Ninilchik. Seward tended to have black cottonwoods and hybrids.

This pattern aligns with the distribution of the coastal rainforest biome (black cottonwood) and the boreal biome (balsam) that meet around the Kenai Mountains. Interestingly, Cooper Landing and the highway corridor along Six Mile Creek hosted the whole spectrum of cottonwood.

The Kenai National Wildlife Refuge has a congressionally mandated purpose “to conserve fish and wildlife populations and habitats in their natural diversity.” Biological diversity is an important theme in conservation.

Aldo Leopold, the father of game management, believed our land ethic as natural resource managers should include “keeping every cog in the wheel.” He believed it was crucial for “intelligent tinkering” because we may not understand how each species contributes to the whole ecosystem or how each species may contribute as conditions change.

The Kenai sits where two biomes meet and this unique geography blesses us with more cogs. My hope is the diversity we have here on the Kenai will help our landscape be resilient and adaptive long into the future.

Understanding the patterns of diversity today is a prerequisite to understanding which species are winning and losing in the hybrid zone as our climate changes.

Dawn Robin Magness is an ecologist at the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge.

Previous Refuge Notebook articles can be viewed on our website http://kenai.fws.gov/. You can check on new bird arrivals or report your bird sighting on the Kenai National Wildlife Refuge Birding Hotline 907-262-2300.